Emanuele Gambula – Lexify 04.09.2024

Introduction

Since the advent of Bitcoin in 2009, the rise and adoption of cryptocurrency have sparked numerous legal debates, particularly around the nature of these digital assets and whether they can be classified as property that can be held on legal structure such as trust. In 2023 a pivotal development in this area comes from Singapore, where the High Court has provided clarity on this matter through the case ByBit Fintech Ltd v Ho Kai Xin and others [2023] SGHC 199 (the “ByBit case”). On the other hand, the Law Commission of England and Wales (the “Law Commission”) has recently undertaken an extensive review of how private law, particularly personal property law, applies to digital assets.

This article has the aims to explore the new draft Bill concerning the categorization of digital assets as personal property under the Law of England and Wales and how this intersects with the previous and one of the most crucial cases on cryptocurrency and property within the common law legal system.

The ByBit Case

The ByBit case revolved around the cryptocurrency United States Dollar Tether (“USDT”), a type of stablecoin that maintains a value pegged to the US dollar. Unlike more volatile cryptocurrencies, USDT’s value remains stable, providing holders with a contractual right to redeem their tokens for an equivalent amount in US dollars. This characteristic of USDT played a central role in the legal arguments presented in the case.

The background of the case involved ByBit, a company operating a cryptocurrency exchange, which compensates its employees in a mix of fiat currency and cryptocurrency. The defendant, Ms. Ho, was entrusted with the responsibility of processing payroll for ByBit’s employees. However, in September 2022, ByBit discovered unusual transactions involving more than 4 million USDT that had been transferred to four different cryptocurrency wallets between May and August of the same year. Further investigation revealed that Ms. Ho was linked to these wallets and had engaged in significant luxury spending shortly after these transactions occurred.

Faced with these findings, ByBit initiated legal proceedings against Ms. Ho, claiming ownership of the misappropriated USDT and arguing that Ms. Ho held the cryptocurrency as a constructive trustee, having acquired the assets through fraudulent means.

The High Court’s Ruling

This case offered critical insights into how cryptocurrency, particularly stablecoins like USDT can be treated under trust law. In fact, the Singapore High Court ruled that USDT is indeed property capable of being held on trust. This ruling was based on several key considerations that reflect the evolving understanding of digital assets within the legal framework.

Firstly, the court noted that crypto assets like USDT are reflected on company balance sheets, signifying their recognition as valuable assets within corporate financial structures. Additionally, digital assets can be identified and segregated, a point underscored by guidelines from the Monetary Authority of Singapore, which has provided a framework for managing and classifying such assets.

Moreover, the court highlighted that Singapore’s Rules of Court 2021 explicitly recognize cryptocurrency as “movable property” that can be subject to enforcement orders. This recognition aligns with the broader ability of crypto assets to be traded and valued similarly to traditional forms of property. In assessing the nature of USDT, the court also applied the test for property rights as established in the case National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth [1965] 1 AC 1175 (i.e. indicia of property – see paragraph 4 below). Here, it was determined that crypto assets meet the criteria for being classified as property under the law.

Another crucial aspect of the ruling was the classification of cryptocurrencies as “things in action,” a legal term that in common law refers to property rights over intangible objects (see paragraph 4 below). This classification is significant as it places cryptocurrencies within the broader category of assets that can be legally protected and enforced.

A different approach: new Draft Bill in UK on digital asset

In 2024, according to the Law Commission report and draft Bill concerning the categorization of digital assets as personal property under the Law of England and Wales, digital assets, such as crypto-tokens, do not fit neatly into the established categories of personal property within common law[1]. Traditionally, personal property is classified into two categories:

- things “in possession”: These are tangible, movable, and visible objects that can be physically possessed, such as a bag of gold. Possession of a thing gives its possessor a property right which is enforceable against the world (in rem).

- things “in action”: These refer to intangible rights that can only be claimed or enforced through legal action, enforceable against a particular party (in personam). For example, debts or shares in a company.

While things in possession exist regardless of whether anyone lays claim to them, and regardless of whether any legal system recognizes or is available to enforce such claims, things in action have no independent form and exist only insofar as they are recognised by a legal system.

Some legal scholars argue against the recognition of digital assets as property or suggest they should be classified as things in action. Specifically, crypto-token are “the right to the unique data strings on a particular distributed ledger, or put slightly differently, the right to have unspent transaction output (UTXO) locked to a public address with a particular ledger”.

Conversely, the Law Commission claims that digital assets, particularly those like crypto-tokens including but not limited to Bitcoin, do not conform to the category of “things in possession” and “things in action”, rather cryptoassets possess unique attributes that warrant their classification as a separate category (better a third category). They are intangible and cannot be physically possessed, yet they exist independently of legal claims and can be used and enjoyed directly by their holders[2].

The ByBit case and the Draft Bill of Law Commission

It is worthy to note that the ByBit case was profound and wide-reaching, in fact many scholars during the discussion of the new Draft Bill mention it among other cases such as Hong Kong: Re Gatecoin Ltd [2023] HKCFI and New Zealand: Ruscoe v Cryptopia Ltd [2020] NZHC claiming that ByBit marked the first time a common law court had definitively categorized cryptocurrency as property, specifically as “thing in action.” This precedent set the stage for enhanced legal protection for cryptocurrency holders in Singapore, offering them legally enforceable rights over their digital assets.

Furthermore, the decision provided a much-needed clarification of the legal nature of crypto assets within common law jurisdictions. By recognizing cryptocurrencies as property, the court had laid the groundwork for future legal developments in this area, particularly in relation to the enforceability of rights over such assets.

This decision also reflected Singapore’s broader trend of adopting a practical and commercially oriented approach to the regulation of cryptocurrency. The ruling aligned with the country’s “crypto-friendly” legal environment, signaling a willingness to integrate established legal principles into the novel and rapidly evolving realm of digital assets.

On the other hand, now, the Law Commission recommends the creation of a third category of personal property to encompass digital assets[3]. This recommendation is based on the recognition that digital assets have unique characteristics that distinguish them from traditional personal property. The Law Commission’s draft Bill aims to confirm the legal status of digital assets as property, thereby providing greater legal clarity and protection for the token holders.

If a particular type of asset satisfies the various “indicia of property” identified by courts and commentators[4], the law should – and the Law Commission argues already does – regard it as property, specifically the asset should be (a) definable; (b) identifiable by third parties; (c) capable in its nature of assumption by third parties; (d) with some degree of permanence or stability; (e) excludability; (f) rivalrousness; (g) separability; and (h) value.

The concept of rivalrousness is particularly important. A resource is rivalrous if its use by one person necessarily prejudices the ability of others to use it simultaneously. This characteristic is crucial in determining whether digital assets can attract property rights. In this regard, the Law Commission clearly stated that “any property rights in relation to such assets can be asserted by the use and enjoyment of the things themselves and by the exclusion of others from them. This is one of the fundamental underlying innovations of crypto-tokens, because it is all achieved through software where this was not previously possible”[5].

Furthermore, the Law Commission specified that, when the blockchain, is used as a means to record certain off-chain assets using tokens e.g. for the tokenization of real-world asset, then “legal rights (as opposed to things such a crypto-token) […] will be treated as things in action by the law”[6]. This is not certainly new in other jurisdictions, especially in Switzerland, where it has been stated that “if ownership of a thing and direct possession diverge, property relationships may be mapped onto a decentralized register”[7]. It has been demonstrated that that, according to Swiss private law, digital assets could represent property rights and could even facilitate the transfer of ownership rights without the need for physical delivery of the asset[8].

The Draft Bill and its implication

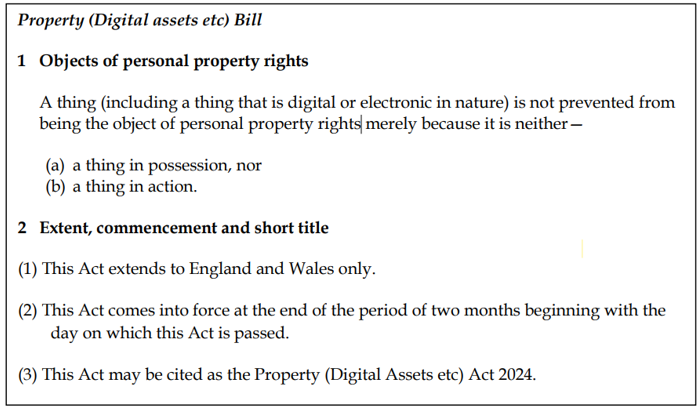

As provided in the new draft Bill (reported below), the Law Commission seeks to formally recognize digital assets as capable of being objects of property rights.

Therefore, a thing will fall within this third category if:

(i) it attracts property rights in terms of existing property indicia (see Paragraph 5 above); and

(ii) cannot be deemed as a thing in possession nor in action[9].

Conclusion

This is a divergence between the Singapore High Court’s ruling in the ByBit case and the Law Commission’s Draft Bill regarding the legal status of digital assets in UK. The Singapore court’s decision to classify cryptocurrencies, particularly stablecoins like USDT, as “choses in action” aligns with traditional property law principles, thereby offering enhanced legal protection to holders of such assets. In contrast, in UK the Law Commission’s proposal to create a novel third category for digital assets underscores the unique characteristics of these assets, which, according to the Commission, do not fit neatly into the existing categories of “things in possession” or “things in action.”

In this case the new Draft Bill seems to diverge from the judicial dicta[10] of Singapore High Court’s ruling, according to which digital assets were ruled to be “things in action”[11]. Such an approach reflects the evolving nature of law in the face of technological advancements.

[1] The doctrine that courts should follow precedents set by higher courts or previous rulings, is a cornerstone of common law.

[2] Hong Kong: Re Gatecoin Ltd [2023] HKCFI and New Zealand: Ruscoe v Cryptopia Ltd [2020] NZHC.

[3] See Law Commission, Digital asset as personal property: Supplemental report and draft Bill, cit., par. 3.32.

[4] This is not a new proposal as it has been taken into consideration with emergent forms of intangible things such as milk quotas. See Swift v Dairywise, 2000.

[5] Such indicia of property are described by Lord Willberforce in National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth,1965.

[6] See Law Commission, Digital asset as personal property: Supplemental report and draft Bill, cit., par. 2.38.

[7] See Law Commission, Digital asset as personal property: Supplemental report and draft Bill, cit., par. 3.48.

[8] Federal Council, Report of the Federal Council of December 7, 2018 “Legal framework for distributed ledger technology and blockchain in Switzerland”, p. 65.

[9] L. Schlichting, A. Borri, R. Salvioni, Tokenization of Property Rights.

[10] Please note that the Law Commission uses the term “cryptoasset” or “crypto-token” referring to a thing “which has been “linked” or “stapled” to a legal right or interest in another thing. The crypto-token exists as a notional quantity unit manifested by the combination of software by network of participants and network-instantiated data”. In addition, the Law Commission defines cryptocurrencies (e.g. Bitcoin) as a “subset of crypto-token designed to act like money/currency”. See also the definition of “crypto-asset” according to the article 3(1)(5) of the EU Regulation 2023/1114 (“MiCA Regulation”): “a digital representation of a value or of a right that is able to be transferred and stored electronically using distributed ledger technology or similar technology”.

[11] See Law Commission, Digital asset as personal property: Supplemental report and draft Bill, Law Com No 416, 2024, par. 2.36 et seq.

Connect with us

Thank you for taking the time to read our article. We hope you found it informative and engaging. If you have any questions, feedback, or would like to explore our services further, we’re here to assist you.

Follow Us

Stay updated and connected with us on social media for the latest news, insights, and updates:

Linkedin Lexify